Property Tax Commission Asking The Wrong Question

The preliminary report of findings and recommendations of the New York State Commission on Property Tax Relief proves that if you ask the wrong question, the response will always be flawed.

The Commission’s preliminary report purports to tell us how we can maintain our state’s commitment to excellent public schools in every community, while reducing property taxes. This is the wrong question for two reasons. First, only a portion of New York’s local support for public education comes from property taxes. The report fails to address the burdens of taxpayers in New York City, Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse and Yonkers, where there is no direct property tax levy to pay for schools.

Second, the report implicitly acknowledges that its proposed limits on local property taxes will require a significant increase in state aid for schools. It cites the history of school funding in Massachusetts—where exactly this happened—as a success story. Yet the report fails to provide serious suggestions to fund increased state aid. Instead, it offers some ideas for “changing state law and mandate relief.”

Some of the proposals are very good, such as creating incentives for school districts to consolidate. Some, like the proposed requirement that local government and school district employees contribute at least 10% (for individual coverage) and 25% (for dependent coverage) towards the cost of health insurance, are simply anti-worker. Many—a “regional collective bargaining contract” which districts may choose to join—are politically impossible. There is no way that the Commission’s suggestions—even if politically feasible—would generate the money needed to insure that its thoughtful proposals for a tax cap and circuit breaker would not have a severe impact on New York’s poorest school districts.

In essence, the Commission’s report is an unfunded mandate in reverse. Its proposals would inevitably force the state to raise substantial additional funds for school aid. But it offers no realistic proposal to raise these funds.

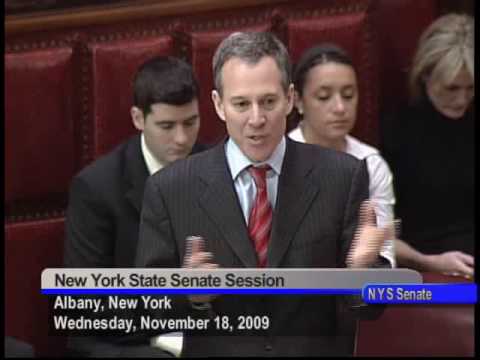

If the additional state aid the Commission’s proposal would require is to come from New York State’s general fund—largely sustained by the taxes of New York City residents—I will have a hard time explaining to my constituents why they are paying for a program that reduces the taxes for New Yorkers who support local schools through the property tax, but provides no help for those of us who do not.

The Commission, which has worked hard and amassed a great deal of information in the course of its hearings, needs to shift its focus as it moves towards its final report. We need proposals that take into account all of the New York State and local taxes that fund education. And we need a fiscally and equitably balanced plan to fund high quality schools in every community, no matter how poor.