New York Lawmakers, Economists Mull Alternate Education Funding

Senator Brooks at Senate hearing on possible alternatives for education funding

ALBANY — Everyone pretty much agreed on one thing during Wednesday’s Senate hearing on possible alternatives for education funding: Property taxes are universally unpopular but they will likely continue as a mainstay of school support in New York.

“It is consistently the least popular tax,” said Thomas Downes, a Tufts University economist who was among the speakers at a hearing led by Senate Education Chairwoman Shelley Mayer, D-Yonkers, and Budget Chairman Brian Benjamin, D-Manhattan.

But they are also the most stable over time, since, unlike sales or income taxes, they don’t go up and down with the inevitable economic cycles.

And since homeowners can ultimately lose their houses if they don’t pay, they will forego other expenses to make sure the property taxes are covered.

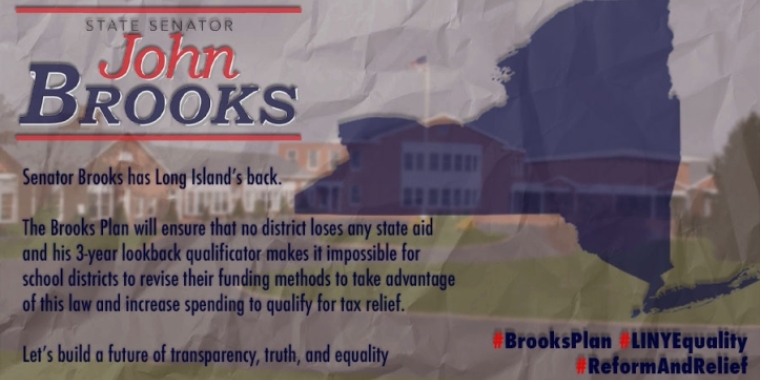

“One of the things (homeowners) make sure they are going to pay is their (property) taxes,” said Sen. John Brooks, D-Long Island.

“(Property tax) is a stable and predictable source of funding and it is less subject to economic whims than sales or income tax,” said Emily Parker, senior policy analyst at the Education Commission of the States.

The trouble is those taxes tend to rise with home values, even if incomes aren’t keeping pace. “Their homes are appreciating greatly over time. The incomes are not,” Brooks said of many of his constituents, including some who opt to leave the state or simply walk away from their houses which leads to “zombie homes.”

Moreover, with the state’s 2 percent property tax cap becoming permanent this year, the state’s vast education lobby is looking for alternate streams of revenue. Adding to the challenge is the new $10,000 federal limit on local property tax deductions. Homeowners in high tax areas like Westchester County or Long Island feel the impact of that since they used to be able to write off unlimited amounts of their school and county taxes from their income tax filings. Now they hit a ceiling at $10,000.

There are plenty of ideas to fix this but none of them would be easy to implement, experts said.