My Testimony Before the New York City Council Committee on Small Business Regarding the Small Business Jobs Survival Act

October 22, 2018

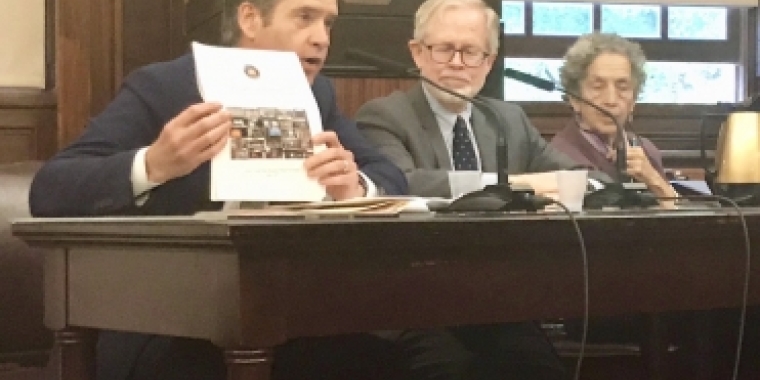

TESTIMONY OF STATE SENATOR BRAD HOYLMAN

BEFORE THE NEW YORK CITY COUNCIL COMMITTEE ON SMALL BUSINESS ON INTRO No. 737-A

October 22, 2018

Thank you Chairman Gjonaj and the Committee on Small Business for this opportunity to testify. My name is State Senator Brad Hoylman and I represent the 27th Senate District, which encompasses the neighborhoods of Greenwich Village, East Village, Chelsea, Hell’s Kitchen, Upper West Side, Columbus Circle, Times Square, East Midtown, East Village, Peter Cooper Village-Stuyvesant Town, Hudson Square and the Lower East Side.

Here is a familiar New York story. It goes like this: A longtime local small business – it could be a diner, a hardware store or a bookstore – closes because it can no longer afford the rent. The space stays vacant until eventually, if at all, the storefront is replaced by a chain. This is a phenomenon that has been referred to as “high-rent blight,” a term coined by Columbia Law professor Tim Wu and discussed by the writer Jeremiah Moss and many others.

I hear this story often from constituents who are concerned about the impact high-rent blight is having on their neighborhoods. The loss of independent businesses, or “mom and pop” stores, and the proliferation of vacant storefronts makes our communities less livable and less pleasant places to be, and the loss in goods and services that cater to the neighborhood causes a strain on our local economy, not to mention an inconvenience for residents.

It’s also just sad to see businesses that have become fixtures in our neighborhoods get pushed out because a landlord can find a higher-paying tenant elsewhere. The examples seem to be everywhere. Who doesn’t remember Coffee Shop in Union Square (which closed on Friday to be converted into a Chase Bank soon)? Tortilla Flats on West 12th Street which opened in 1983? Or Caffe Vivaldi on Jones Street, which closed this summer after three and a half decades?

Last year, I set out to try to help answer the question of what was really going on with high-rent blight and small business vacancies in several areas in my district: on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village and in the East Village and Chelsea. I wanted to see if small business vacancies were really such a big problem, and if so, could we figure any of the causes and could government play a role in making our neighborhoods livable once again?

My office set out to look at the vacancy issue of mom and pop stores by counting and analyzing the number of vacant stores along the major commercial corridors in the 27th Senate District and supplemented this data by speaking to local small business owners and community leaders.

We published the information in a report last year entitled: “Bleaker on Bleecker: A Snapshot of High-Rent Blight in Greenwich Village and Chelsea.”

Here’s what I found after our office took to the streets in April of last year and counted the number of vacant retail spaces along several select corridors. The vacancy rates were:

First Avenue from 10th Street to 23rd Street - 5.756% vacancy rate

Second Avenue from 3rd Street to 14th Street – 6.67% vacancy rate

Eighth Avenue from 15th Street to 22nd Street – 6.52% vacancy rate

Bleecker Street from 6th Avenue to 8th Avenue 18.44% vacancy rate (nearly one in five storefronts were vacant along this corridor)

What’s the problem with this? A high rate of storefront vacancies is historically considered to be the sign of an economically distressed or even crime-ridden neighborhood. In the heart of Manhattan, however, these vacancies are occurring in relatively prosperous neighborhoods, hence the phenomenon known as “high rent blight,” a term coined by Columbia law professor Tim Wu.

High rent blight is a central issue at play in storefront vacancies: It occurs when rents are raised astronomically and suddenly. One study estimates that the average commercial rent in Manhattan increased by 34% from 2004 to 2014 and another shows it jumping 42% from 2012 to 2015.

When mom and pop stores are pushed out because of high rents, landlords it would appear often leave stores empty for long periods of time in hopes of finding a credit-worthy tenant who can pay much higher rent.

These days even chains are not exempt from the phenomenon of high rents leading to vacancies. For example, a Starbucks at 33rd and 5th Avenue closed when a lease deal could not be reached (the space now rents for upwards of $1 million). Another Starbuck’s on 67th and Columbus closed in 2016 after the rent was raised to over $140,000 a month. You know you have a problem, as has been said, when Starbucks can’t pay the rent!

So what do we do about the problem of high-rent blight?

First, on the issue at hand. I’m glad the Small Business Jobs Survival Act is finally getting the hearing it deserves and I want to thank Council Member Rodriguez for reintroducing it. It seems reasonable on its face that landlords would be required to tell commercial tenants at least months before the end of a lease whether they intend to renew or state a valid reason why they won’t. The devil, of course, will be in these details and what constitutes a “valid reason.”

I do think the need for this legislation points to the enormous power imbalance that exists between landlords and tenants, both commercial and residential. Just as the City Council has taken steps to ensure that tenants have legal counsel in housing court, I think the City and State need to consider how best to ensure that small businesses are represented during lease negotiations with their landlords. I’ve heard too many times that a small business simply throws its hands up when the landlord suggests a rent increase rather than try to negotiate a better deal.

Second, we need better data. It’s worth noting that the survey I conducted for my report was undertaken by my office without help from city or state agencies. There is currently no such centralized data on New York City’s storefront vacancy rates, and the absence of this data allows problems to continue unabated. This data should be proactively collected and made publicly available by the City, as has been suggested by members of the City Council. In addition, we need to get a handle on the impact of on-line shopping on New York City’s small businesses. Data is required to understand the so-called “Amazon effect.”

Third, I want to commend the City Council and the Mayor for already taking up this issue last year by raising the threshold for the Commercial Rent Tax for small businesses below 96th Street in Manhattan. The move reduces taxes for 2,700 small businesses and will surely help mom and pop shops. The question is, however, do we need to raise the threshold even higher to help more businesses? And speaking of threshold questions, you have to ask why businesses in Manhattan below 96th are subject to the CRT in the first place, since it puts them at such a competitive disadvantage for businesses located elsewhere in Manhattan and the city as a whole.

And fourth, I encourage you to read my report and look at other suggestions I’ve proposed, such as creating a public registry of legacy business -- small businesses that have been in New York City for at least 30 years, as San Francisco has done, making them eligible for historic tax preservation tax credits or other benefits to be determined.

Or consider expanding formula retail zoning restrictions, which San Francisco has done and has also been pioneered on the Upper West Side by Borough President Gale Brewer. I carry legislation with Assembly Member Deborah Glick that would enable the City to place limits on formula retail uses.

And finally, we should look at something at the State level, such as phasing out tax deductions for landlords with persistent vacancies. While landlords who leave retail storefronts vacant cannot deduct the lost potential rental income they could have received from their state income tax liability, they, like all owners of commercial real estate, are able to receive deductions for depreciation of the property and operating expenses. (That’s how Jared Kushner, by the way, avoids paying taxes!) To create a disincentive for leaving retail storefronts vacant, the State could explore phasing out those deductions, on a sliding scale, for building owners who leave retail spaces vacant for over one year.

There are carrots, too, as well as sticks. In the City of London, for example, commercial building owners who lose their tenants are provided tax relief in the short term, but after three months, the tax relief expires and owners must pay full business rates even if the store is vacant. This is meant to encourage landlords to rent out their space.

Thank you again for the opportunity to testify today on this important issue.