A Soldier Home From War, And A Mother Fighting Hard

CLICK HERE TO VIEW THE LINK TO THE ARTICLE

On Veterans Day, all that Cathy Di Iorio wanted was to have her son back. It was too much to ask for. “It’s not happening — let’s be honest,” she said.

Physically, John Di Iorio has been back for a few years. Back to his parents’ house on Staten Island. Back from active Army duty. Back from Iraq. Back from the roadside explosion that ripped his Humvee apart and rattled his brain, damaged nerves and hurled shrapnel into his spine, thigh and abdominal wall.

“I don’t know all the details,” Ms. Di Iorio said, “because he doesn’t want to talk about it.” She does know that the extent of his injuries was not detected at the time. “They put him back out in the field without knowing there was this shrapnel in him,” she said.

She knows something else, too. Mentally and emotionally, her son is far from back. That’s a road less traveled.

When he visits Veterans Affairs doctors, he insists on going alone. He’s 32, he tells her. He’s a man. A man fends for himself. But later he can’t remember what advice the doctors gave him. “It’s lost in his mind somewhere,” his mother said.

Don’t even get her started on the doctors, she said. She has tried on her own to get information from them, only to “get the runaround.”

“They acknowledge he has the shrapnel in his body, but he has to prove that it came from Iraq,” she said. “That’s where I blow a gasket. Prove? How’s he going to prove that?”

“He’s got a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart. That’s great. But all I want is medical advice — where to go, what’s the right thing to do.”

Like some other New Yorkers, John Di Iorio responded to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. A neighbor of his, a firefighter, had died in the World Trade Center. So Mr. Di Iorio joined the Army and went proudly off to war, even if it was in a country that had nothing to do with 9/11.

The rest of us got to go about our lives. No political leader asked for a comparable sacrifice from us, not for a second. We could dwell unhampered on more immediate concerns, like A-Rod’s millions or the latest on Paris Hilton.

Meanwhile, Cathy Di Iorio teamed up with Christine DeLisa, the mother of another wounded soldier, in a group they called Staten Island Supports Our Soldiers. “The child that you send over is nothing like the child that comes back to you,” said Ms. DeLisa, the organization’s chief executive. Returning soldiers, many of them anyway, are “not at peace with themselves or with anybody around them,” she said. They need help.

All too often, others don’t want to hear any of this. With Christmas coming, Ms. Di Iorio has begun a toy drive for the children of military families on Staten Island. “People don’t want to give,” she said. “They say, ‘I don’t believe in the war.’ Neither do I. But our people are over there. Why should their families suffer?”

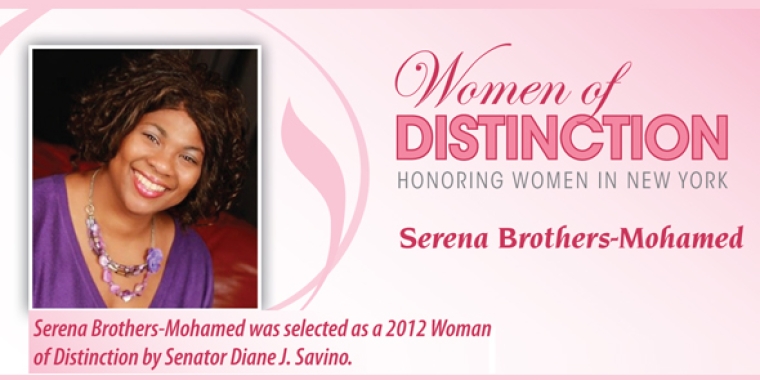

Her frustration poured out over the weekend at a forum on the problems facing America’s newest combat veterans, those returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. The session, held at a Staten Island hotel, was sponsored by Ms. DeLisa’s group, State Senator Diane Savino of Staten Island and the state’s Division of Human Rights.

Waving the flag on Veterans Day is one thing, Ms. Savino said, but critical issues endure beyond the holiday. Stories keep surfacing about soldiers who do not receive proper medical care, who struggle to get disability benefits, who find their old jobs gone, who even end up homeless.

Veterans need to know they have rights, said Kumiki Gibson, the human rights commissioner. “I’m not trying to make anybody feel like a victim,” she said. “It’s not a weakness to insist on your rights.”

But convincing some veterans of that may not be easy. Two dozen of them were expected at the forum. Instead, two turned up. Where had all the soldiers gone?

“It’s the military mind-set: Hardship is part of the job,” said one of the two who showed up, Louis Maniscalco. He is a New York City police officer and National Guardsman who “walked away with just some bumps and bruises” from a year’s tour in Iraq. A prevailing military attitude, he said, is that “if you don’t have it, it’s because you don’t really need it” — whatever the “it” may be, rights included.

Ms. Di Iorio was unable to persuade her own son to attend. But then, she said, he’s not what he once was. Suppressing bitterness isn’t easy for her.

“They took my son from me,” she said. “He’ll never be the same. Never.”