New York Times: 150 Big Businesses Warn Mayor of ‘Widespread Anxiety’ Over N.Y.C.’s Future

More than 150 business leaders in New York City joined together on Thursday to warn Mayor Bill de Blasio that he needed to take more decisive action to address crime and other quality-of-life issues that they said were jeopardizing the city’s economic recovery.

Chief executives of companies like Goldman Sachs, Vornado Realty Trust and JetBlue sent a letter to the mayor portraying a bleak assessment of life in New York City during the pandemic, and suggesting a vote of no confidence in the mayor’s ability to correct it.

The letter asserted that there was “widespread anxiety over public safety, cleanliness and other quality of life issues that are contributing to deteriorating conditions in commercial districts and neighborhoods across the five boroughs.”

And if the mayor did not address those issues, the business leaders warned that people who have left the city would be slow to return because of legitimate concerns over “security and the livability of our communities.”

The letter, which was sent nearly six months after the outbreak forced New York City into a lockdown, represented something of a watershed moment in the fraught relationship between the business community and Mr. de Blasio, a progressive Democrat elected in 2013 who has long portrayed himself as a champion of the city’s poor and working class.

Business leaders had largely refrained from criticizing the mayor and his administration as they fought the coronavirus outbreak. But schools are about to reopen, and companies are following suit: JPMorgan Chase wants some of its senior officials to return to the office starting Sept. 21.

And as that transition continued, the executives grew anxious about what they saw as the city’s deterioration.

They acknowledged the city’s success in containing the coronavirus, but highlighted that “unprecedented numbers of New Yorkers are unemployed, facing homelessness, or otherwise at risk.” They offered to help and advise the mayor on restoring essential services.

The letter might roil the debate over President Trump’s repeated claims that Democratic-run cities have been allowed to “deteriorate into lawless zones” following the George Floyd protests, and is likely to be cited in Republican messaging leading up to the November election.

The letter’s political repercussions may also stretch to the 2021 mayoral race in New York; business leaders have yet to coalesce behind any of the current candidates.

Mr. de Blasio responded in a conciliatory tone, urging business leaders to work with him and arguing that the city needed federal funding and new borrowing capacity.

“We need these leaders to join the fight to move the city forward,” the mayor said on Twitter.

The letter reflected a divide in how people perceive the effects of the outbreak, which has killed more than 20,000 city residents and left hundreds of thousands unemployed. While some New Yorkers have departed for the suburbs or to vacation homes, many who have remained have taken issue with the portrayals of a city abandoned and overrun by disorder.

Indeed, signs of normalcy have returned, from outdoor dining to socially distanced gatherings at parks. By the end of the month, in-person education at public schools and indoor dining will return. The main reason the city has been able to start reopening is that the infection rate has remained low, with only about 1 percent of virus tests coming back positive.

“We’re grateful for the business community’s input, and we’ll continue partnering with them to rebuild a fairer, better city,” Bill Neidhardt, a spokesman for Mr. de Blasio, said in a statement. “Let’s be clear: We want to restore these services and save jobs, and the most direct way to do that is with long-term borrowing and a federal stimulus. We ask these leaders to join in this fight because the stakes couldn’t be higher.”

The de Blasio administration has had to make cuts to city services in an effort to close a two-year, $9 billion budget gap. In the letter, the business leaders offered no specific solutions for how he might balance the budget.

Kathryn Wylde, the president of the Partnership for New York City, said in an interview that the letter had been in the works for about a month, as many of the executives’ companies were preparing to have some workers return to the office.

“All these employers are committed to the city, they want to see economic recovery, but they’re getting pushback from their employees about, will the city be safe, will the city be clean,” Ms. Wylde said.

One leader who signed the letter, Scott Rechler, chief executive of RXR Realty, placed the blame squarely on Mr. de Blasio, who is in his second and final term.

“The problem right now is leadership,” Mr. Rechler said in an interview. “We need a strong leader to address these problems, to encourage people to feel comfortable coming back to the city.”

Another signatory to the letter, Douglas Durst, chairman of the Durst Organization, a major city landlord, said the city must close its budget deficit while maintaining city services.

“It’s hard to bridge that gap, but I think that’s why it would be helpful to bring in the private sector to figure out what’s the best way to do it,” Mr. Durst said in an interview.

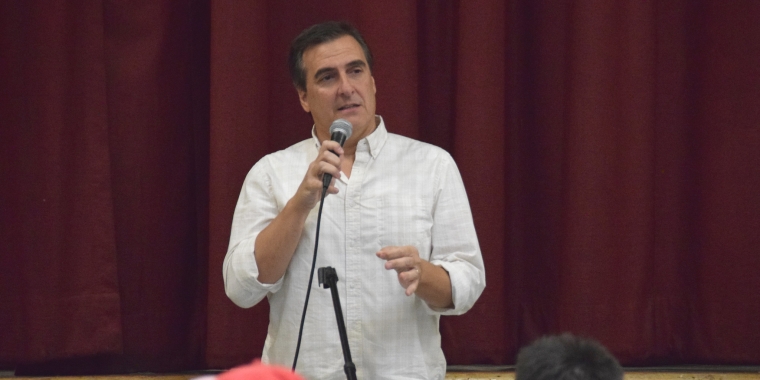

Michael Gianaris, a Democratic state senator from Queens, said it was hypocritical for business leaders to call for better city services without helping to pay for them through higher taxes on the wealthy.

“Where do they think this money comes from?” he said. “If these business leaders are calling for better sanitation, they must know that comes from money we don’t have.”

Mr. de Blasio has often had a strained relationship with the business community and has repeatedly called for higher taxes on millionaires. Asked over the summer why he did not work more closely with business leaders, Mr. de Blasio quoted Karl Marx and disparaged the annual Davos gathering of global elites.

“We will work with the business community, but the city government represents the people — represents working people — and mayors should not be too cozy with the business community,” Mr. de Blasio said in a radio interview on WNYC.

Another leader who signed the letter, Barry M. Gosin, the chief executive of Newmark Knight Frank, a commercial real estate firm, said Mr. de Blasio needed to work with business leaders.

“The business community is not an enemy of the people,” he said. “We are people. We are part of it.”

The letter came two days after Mr. de Blasio, heeding concerns from Upper West Side residents, announced he would move hundreds of homeless people from a hotel in the upscale neighborhood.

That same day, his own sanitation commissioner, Kathryn Garcia, called his cuts to the department’s budget “unconscionable” as she resigned. According to Ms. Garcia, the department has lost some 400 positions through attrition.

In recent weeks, real estate executives and corporate leaders have expressed frustration at what they view as rising levels of dirt and disorder in city streets, particularly in Midtown Manhattan, where the absence of both tourists and office workers has left the streets eerily empty.

While state and city guidelines permit offices to be filled to half-capacity, most buildings are below 10 percent occupancy. Companies have for the most part not required workers to return, and few have.

But City Hall has not been receptive to the concerns, according to a person with direct knowledge of the discussions, because the de Blasio administration has been focused on reopening schools.

The economic crisis spawned by the pandemic has drawn comparisons to the New York City fiscal crisis of the 1970s and other difficult chapters in the city’s history.

In response to the executives’ letter, William J. Bratton, a police commissioner under Mr. de Blasio, compared his former boss to David Dinkins, another mayor who he said had failed to address crime and quality-of-life issues in the 1990s.

“Déjà vu, all over again,” Mr. Bratton said.