WSJ: NYC Co-Op Boards Would Have to Explain Why They Deny Buyers, Under New Bill

New York state legislators are looking to make residential co-op boards more accountable for decisions to reject potential buyers; Park Avenue in New York City. Photo: José A. Alvarado Jr. for the Wall Street Journal

On April 11, 2021, Will Parker of the Wall Street Journal reported on Senator Kavanagh's proposed legislation, S2874. The full text of the article is below; the original version is available via the link above.

_______________

By Will Parker

April 11, 2021 12:00 pm ET

State lawmakers are proposing new rules that would require New York City co-op boards to state why they rejected a potential apartment buyer, seeking to end a longstanding practice that critics say facilitates housing discrimination.

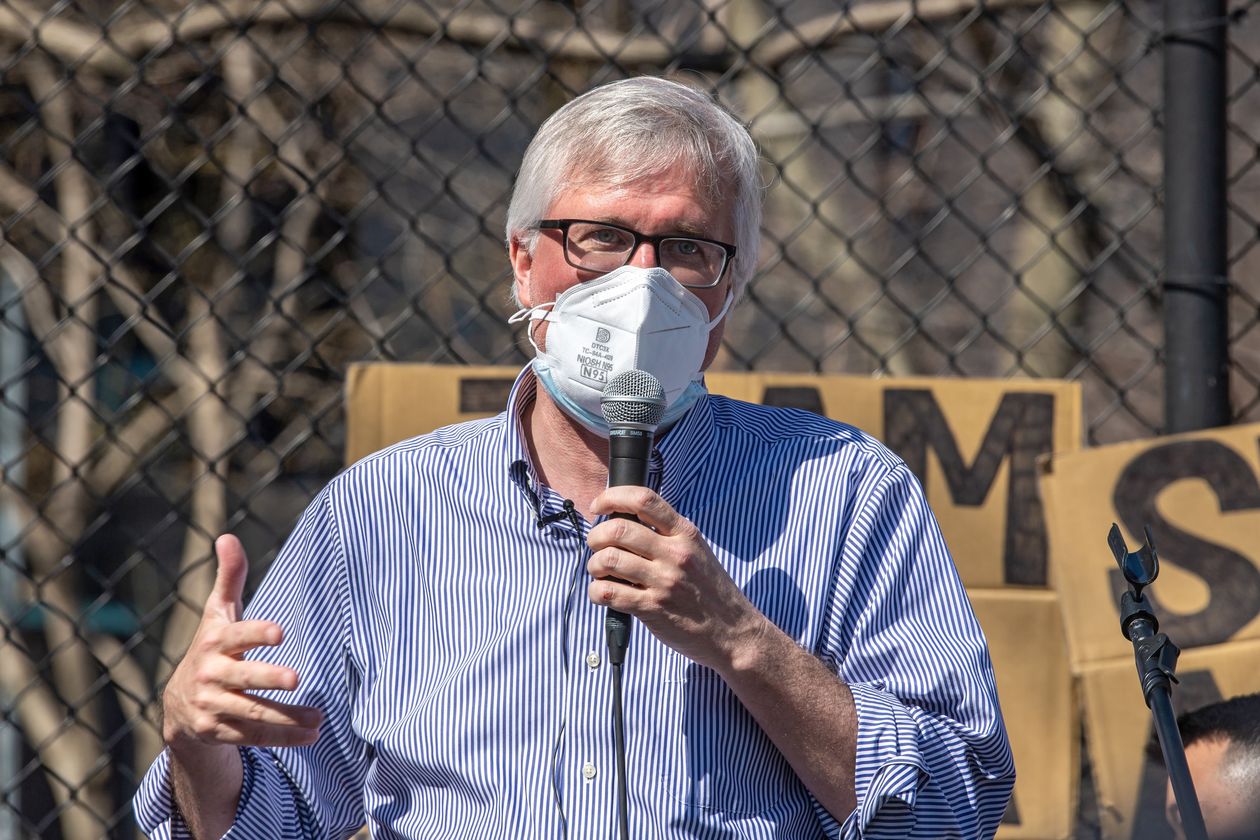

The State Senate bill, sponsored by housing committee chair Brian Kavanagh (D., Manhattan), says residential co-op and condominium boards would have to provide written explanations when they decide to turn down applicants who want to purchase at their building. Under current law, boards aren’t required to offer any reason, and they rarely do so.

Democrats have introduced a version of this bill many times in the past, but it has failed because some lawmakers have been sympathetic to objections from co-op boards, who fear opening themselves up to more litigation. The sponsors believe it has a better chance of passing in the now solidly progressive New York State Legislature, and they hope to bring it to a vote sometime this year.

Co-op residents don’t own their apartments, but rather buy shares in a co-owned building, a system that has been around since the late 19th century. By co-owning buildings with fellow tenants, residents felt they could have more control over renovations and over who could be their neighbors. Co-ops were often more financially stable than other types of buildings during economic downturns, because they could deny sales to potential buyers who had to borrow heavily to buy in.

Co-op boards can reject prospective residents for any reason that isn’t protected under local and federal antidiscrimination laws. But fair-housing advocates say a board’s lack of accountability or transparency into the decision-making process opens the door to discrimination, based on a potential buyer’s race, sexual orientation or religion.

Over the years, rejected applicants have sued city co-op boards for illegal racial, religious and other forms of discrimination. A decade ago, Alphonse Fletcher Jr., a Black hedge-fund manager, accused the co-op board of the landmark Dakota building on Central Park West of racially discriminating against him and other prospective buyers, after the board rejected his application to buy an additional apartment in the building; the suit was later dismissed.

Some real-estate attorneys and brokers think the proposed bill could lead to more lawsuits against boards, if applicants don’t believe the official reason.

“I am concerned that something like this may actually create fodder for somebody who wants to make a claim of discrimination where the reasons may be legitimate,” said Steven Wagner, a real-estate attorney. He cited weak financials or an application that lacks required documents as legitimate concerns about an applicant.

Mary Ann Rothman, executive director of the Council of New York Cooperatives and Condominiums, a lobbying and advocacy group, said she fears a new law would lead to a flood of lawsuits, which could ultimately dissuade more residents from serving on co-op boards. “The vast majority of co-ops function like little democracies and work well,” she said. “People who serve on the board serve as volunteers and are protecting their own home and community.”

Assemblyman N. Nick Perry, the bill’s sponsor in the State Assembly, said that although discrimination is much less common than in the past, more transparency is still needed to make sure co-op boards aren’t acting on bias.

“I think it will always be the case. It’s not always intentional,” he said. “The intent is to prevent discriminatory decisions.”

Co-ops’ reputation for exclusionary behavior has hurt the market for these apartments over the decades, said Donna Olshan, president and owner of brokerage Olshan Realty Inc. Although about 75% of the for-sale housing market in Manhattan is still made up of co-ops, developers in recent decades have built few new ones, opting instead for condominiums, which typically have less restrictive rules, making them more attractive to buyers.

As of the first quarter of 2021, the average price per square foot for a condominium apartment was $1,714, compared with $1,054 for a co-op, according to a report from brokerage Douglas Elliman.

“The gap between the value of a co-op and the value of a condo continues to grow,” Ms. Olshan said. Making the co-op application process more transparent, she said, “will unlock value. And it will be fair and less discriminatory.”

New York City’s Commission on Human Rights fields complaints of co-op board discrimination. A spokesperson said co-op claims make up a small portion of housing-discrimination claims. Between June 2019 and June 2020, the commission received more than 500 housing-related inquiries, most of them related to disabilities, and with 43 related to citizenship status and 15 related to color, according to the commission’s most recent annual report.

The proposed bill also would require co-ops to spell out their application and acceptance policies at the time of application and to let applicants know if they were approved within 90 days of completing their application.

Write to Will Parker at will.parker@wsj.com

###