Industrial Development Agencies Compete to Cut Business Breaks with ‘Legal Corruption’

A rendering of the facility Medline Industries, a healthcare supplies company, sought to build with a tax break from the Montgomery Industrial Development Agency.

In January 2019, Medline, an Illinois-based distributor of medical supplies with more than $10 billion in annual sales, submitted an application to the Montgomery Industrial Development Agency, requesting financial assistance to construct a new warehouse in Orange County. Medline sought a 15-year, $17 million exemption on property taxes, as well as an $8 million exemption on sales taxes, in order to defray the costs of relocating to Montgomery. Tasked with attracting new businesses, the Montgomery IDA was empowered by the municipal government to grant Medline such exemptions, easing the company’s short-term relocation costs to, hypothetically, improve the town’s long-term economy.

But there was a hang-up: Medline already had a warehouse in Orange County, 20 miles away from Montgomery, in Wawayanda. The company had already received nearly $3.6 million in tax exemptions from the Orange County Industrial Development Agency since constructing the warehouse in 2008. When those exemptions expired in 2019, Medline would begin paying its full tax assessment—unless they could find exemptions elsewhere, like in Montgomery.

(Both IDAs declined or failed to respond to interview requests from The River.)

“It’s one thing to attract a company from another state to bring jobs to Orange County that aren’t already there,” says New York State Senator James Skoufis (D-Cornwall), who led an investigation into Industrial Development Agencies in 2019. “It’s another thing when the jobs are already here—and we’re proposing to grant an additional 10-plus years of property tax breaks for jobs that are already here, within the very county!”

Although Skoufis’s investigation drove Medline to abandon its application to the Montgomery IDA, it illustrates just one of the issues surrounding Industrial Development Agencies, which are intended to improve local economies throughout New York State by attracting new businesses, thereby increasing jobs and tax revenues. According to critics, however, IDAs are offering exemptions to companies that should not qualify, padding their profits at the expense of taxpayers.

“A Race to the Bottom”

IDAs were introduced in New York State by the Industrial Development Agency Act of 1969, which allowed for their creation as public benefit corporations serving localities and their residents. Today, there are 109 IDAs at the county, city, town, and village levels throughout New York State, managing 4,320 active projects worth $109 billion. Each agency is empowered by its respective locality to grant businesses a variety of incentives, but most often exemptions on property taxes, known as Payment In Lieu of Taxes, or PILOT, agreements. Their ultimate goal should be to create and retain jobs. But that’s not always what happens, says Jeff Pearlman, director of the Authorities Budget Office, which oversees IDAs statewide.

“Today, creating and retaining employment is not the focus of the IDA,” says Pearlman. “Instead, IDAs are building market-rate and senior housing, IDAs provide benefits to mixed-use and retail development, and IDAs are supporting alternative energy projects like solar and wind farms.”

While Pearlman concedes that some of these projects are laudable, he sees their sprawl as indicative of the model’s waywardness. A survey of IDAs conducted by the Authorities Budget Office in 2020 found that only 26 percent of approved projects were in manufacturing, while the rest were in retail, office space, housing, or mixed-use projects—in-demand sectors that should not require incentives at public expense. It’s a sentiment that Skoufis echoes, especially in regards to warehouses like those of Medline or Amazon, to whom the Montgomery IDA extended more than $25 million in tax exemptions via a real estate developer, USEF SAILFISH, LLC, in 2020.

“You have all these distributors who are desperate to get hubs within an hour and a half of New York City, centrally located along I-84 and the New York State Thruway and all these major thoroughfares that are in the Hudson Valley,” says Skoufis. “This isn’t a matter of trying to lure a business to our region to create jobs and we’ve got to incentivize them. They’re desperate to come to the Hudson Valley! And yet we still see IDAs incentivizing these warehouses. It makes no sense.”

Part of the problem is that IDAs can exert downward pressure on tax revenues, rather than shoring them up. In the competition to attract businesses, the agencies themselves are incentivized to offer greater tax exemptions, creating a scenario where the municipalities that “win” are the ones that lose the most. Such was the case in Hempstead, Nassau County, where local tax jurisdictions lost $6.5 million in revenue in 2016 due to overly generous exemptions given to Macerich, developer of Green Acres Mall and Green Acres Commons, as detailed in the aforementioned investigation led by Skoufis.

“It’s becoming a race to the bottom, oftentimes, between IDAs,” explains Skoufis. “And the biggest loser, when that happens, is the taxpayer.”

“Legal Corruption”

Beyond the sprawl of IDAs today, critics also point to their composition as a potential source of “legal corruption,” as Skoufis describes it. Each agency is made up of volunteer board members, who are typically appointed by the respective municipality and vote on the applications for tax exemptions submitted by businesses. There is currently no prohibition on elected officials themselves serving on IDAs, which creates the opportunity for quid pro quo transactions, such as politicians trading exemptions for campaign contributions.

“They get to campaign season and they pull out their rolodex,” says Skoufis of elected officials who sit on IDA boards. “They go through all of the companies that they voted to give huge tax breaks to. They call them and say, ‘You know, remember that PILOT I gave you 10 years ago?…By the way, I’m now running for state senate and I could use a $5,000 campaign contribution. What do you say?’ There is an inherent conflict in an elected official serving on an IDA board.”

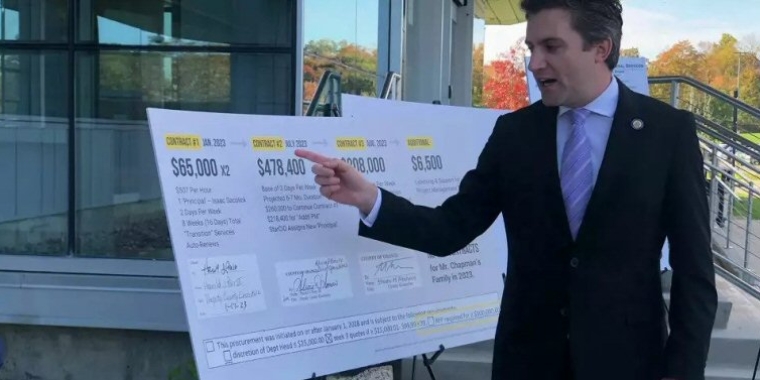

IDA board members are required to report more immediate conflicts of interest to the Authorities Budget Office, but a recent investigation by the Orange County District Attorney and New York State Comptroller into the Orange County IDA illustrates how even those requirements can go ignored. In June 2021, three former agency members pleaded guilty to concealing conflicts of interest, allowing them to direct more than $1 million in funds via contracts to a business that they either owned or were employed by. The three agreed to pay restitution to the IDA, but faced no jail time—an issue that local Democrats took with the plea negotiated by Orange County District Attorney, David M. Hoovler, a Republican.

“The laws relating to larceny are fairly straightforward,” Hoovler responded to critics in a press release, “but the laws that relate to this case are less so.”

“One Leg of the Three-legged Stool”

The laws related to IDAs are, however, rapidly changing. The investigation led by Skoufis in 2019 directly inspired Senate Bill S88, which increases IDA transparency by requiring them to livestream and post video recordings of their meetings and hearings, and was signed into law last August. Further reform was expected in 2020, but derailed by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Still, Skoufis expects more of a reform package to make its way through the state legislature next year, including bills prohibiting IDAs from soliciting businesses from other parts of New York State, restricting elected officials from serving on IDAs, compelling IDAs to issue notice to all jurisdictions whose revenues may be affected by tax exemptions, and other changes aimed at improving accountability and transparency.

Despite the state legislature’s proposals, reigning in IDAs remains an uphill battle, if the Authorities Budget Office’s efforts are any indication. Following complaints about IDAs from state legislators and local tax jurisdictions, the office was created by the Public Authorities Accountability Act of 2005 and further empowered to oversee IDAs by the Public Authorities Reform Act of 2009. Today, the Authorities Budget Office provides training to IDA board members, but also enforces compliance with reporting. The office does not have prosecutorial powers, but can refer cases to district attorneys or the attorney general. Coupled with the 2017 appointment of Pearlman, an attorney specializing in government affairs and litigation, as director of the Authorities Budget Office, scrutiny of IDAs is now perhaps greater than ever before.

Nevertheless, some IDAs are attempting to dodge oversight through legal loopholes. The Saratoga Economic Development Corporation and the Orange County Partnership are currently arguing in state court that they are a “private-sector, not-for-profit, consulting firm” or a “section 501(c) corporation to market economic development,” respectively, and thus exempt from Authorities Budget Office oversight. Pearlman and his office disagree.

“These charities affiliate with the local IDAs through exclusive arrangements, fee sharing, and other funding systems to attract and retain businesses that ultimately receive IDA financing and tax exemption benefits,” says Pearlman. “They serve as one leg of the three-legged stool that makes up a municipal economic development operation: a partnership between the not-for-profit corporation, the municipality, and its regional IDA—all to serve the public.”

(Both the Saratoga Economic Development Corporation and Orange County Partnership failed to respond to multiple interview requests from The River.)

The two court cases, Saratoga Economic Development Corporation v. State of New York Authorities Budget Office and Orange County Partnership Inc. v. State of New York Authorities Budget Office (the latter on appeal), have yet to be scheduled for hearings owing to delays stemming from the pandemic. When they do have their day in court, losses for the Authorities Budget Office could significantly rollback IDA accountability and transparency throughout New York State, casting an even more opaque pall across activities already marred by corruption.

“These charities are exactly what the state legislature intended the Authorities Budget Office to identify and require to be more transparent and accountable,” says Pearlman. “If they are permitted to remain private in their activities, we would see a proliferation of them across the state, no longer holding public meetings or reporting on their business and financial activities. Having such entities operate privately in the public economic development domain would keep elusive much of the activities about how state and local public benefits are provided for economic development.”

Skoufis, too, acknowledges that the fight to reign in IDAs is far from over.

“We still have more work to do,” he says. “Even beyond the Senate package, there’s a lot more work to do.”