New York special education preschools struggle amid funding roadblocks

For two years, Margi Carter has worked a second full-time job so that she can keep her special education preschool open. Routinely she cut her own salary to make ends meet because state funding was $10,000 less than her actual costs.

But after a decade of struggle to keep open the only such preschool in Essex County, she decided enough was enough. Children’s Development Group of Keeseville is closing on June 30, leaving at least 10 children without a special education preschool placement for next year.

She’s not alone. Seven preschools are closing in New York by the end of this school year, and the funding policies at the state level may make it very hard for them to be replaced.

Some of these preschools — often the only places parents with young special needs children can get care outside the home — are in desperate financial condition, burning through years worth of savings because the state is not covering their actual expenses, the state Education Department said.

Several closing this year cited the inability to make it financially with the rising cost of rent, increasing new student needs and changes in enrollment as students move in and out of the region. Others closed because the owners were retiring. In only one case was there an existing program with space to admit all the students who attended the closing school.

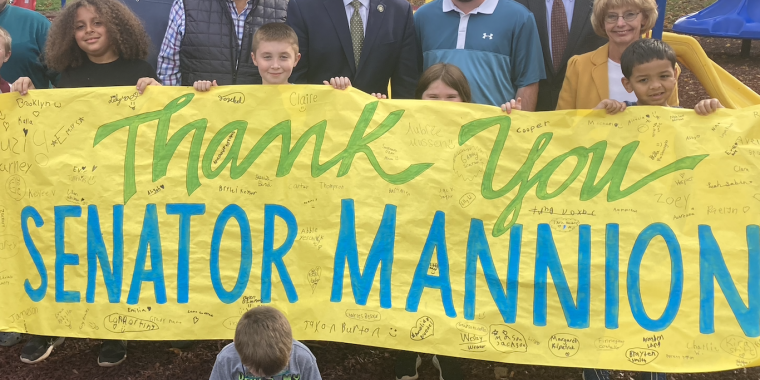

“What is really scary is that these schools are closing. We may be up to as many as 60 schools or programs that have closed down in recent years,” said state Sen. John Mannion, D-Geddes, chair of the state Senate Committee on Disabilities. He has sponsored numerous bills to change the funding process.

“The way we’re doing it is destroying them, it’s closing them,” he said.

The challenges that lead to preschools closing are why it’s difficult to even get one started. The state reimburses them at an estimated rate at first that is widely known to be less than actual costs. Later rates are based on costs, but the process takes so long that the rate doesn’t go up until long after the student who needs services has graduated to kindergarten.

“It just makes it so you can’t do it,” Carter said. “You’re running on rates from two years before. Maybe you didn’t have as many needy kids. Maybe you didn’t need a physical therapist, but this year you do. You’re obligated to provide those services, no matter what the cost is, and maybe two years from now you’ll get a better rate, but that’s too late. You need it now.”

She added that there was enough need that she could have filled a third classroom — but she never expanded because of the funding.

“I couldn’t afford the two programs so to open the third program, no,” she said.

State officials have warned about the situation for years. In 2014, the state Education Department issued a report saying the complex funding formula leads to “dramatically different” rates for children with comparable needs and leaves many preschools in the red.

The report concluded that “concerns exist that this funding gap may ultimately affect the quality and availability of preschool special education service.”

Nine years later, the Board of Regents is still trying to get a better formula. In the meantime, they have received a deluge of requests for waivers, in which a preschool can get its rate increased.

The requests have “increased at an unsustainable rate due in large part to insufficient approved tuition rate growth and inherent flaws in the tuition rate methodology,” the Board of Regents said in a written proposal last year, adding “the resulting delays in funding threaten the viability of providers serving students with disabilities and create vulnerabilities in ensuring available placement options for such students.”

As preschools close, it leaves behind students who need critical early intervention. Counties and school districts try to fill in the gap with at-home therapist visits, but often there are not enough therapists to give every child the number of hours of therapy set in their individualized education plan.

Last year, the state Legislature passed a bill that was intended to address the situation. The bill would “ensure parity across all providers” and provide the same annual rate increase as public schools receive in general funds from the state. The idea was to establish predictable increases each year. It was vetoed by Gov. Kathy Hochul, who said she wanted the special education rate to stay linked to actual costs.

In her veto memo, she said the proposed rate system was “flawed and will not ultimately provide the best system for ensuring special education students receive appropriate services.”

Months later, the state budget included a cost-of-living rate increase of 11 percent for the 2022-2023 school year, fulfilling the promise Hochul made when she vetoed the preschool bill.

However, those who are trying to keep preschools open say the existing way of setting rates is what’s flawed.

The Board of Regents last year asked for $1.5 million over two years to redesign it, which was not approved. In the meantime, the board asked for funding to hire six more staff to get through the backlog of rate reviews, at a cost of $470,031, which was approved.

Funding disparity

When Abilities in Wilton, which abruptly closed this year, expanded to two integrated preschool classrooms, the state granted a provisional rate of $91.60 per child per day. The actual cost was about $159, owner Valerie Keen said.

Other special education preschools in southern Saratoga County, which had existed for decades, had rates of $129 to $139.

The provisional rate is also used when existing preschools expand.

“I have a new classroom that we opened in 2020,” said Sheri Canfield, owner of Spotted Zebra in Albany. “We are operating at a rate that does not support that classroom.”

She said state officials told her that they wouldn’t approve the classroom unless she had enough in savings to run the program for a year. She wasn’t surprised; she said that’s standard policy.

“It’s a horrible process. It’s so difficult for business owners,” especially those trying to open new programs, she said, adding, “We can make it work because we have existing programs.”

She wants more programs to open, because the need is so great.

“We are seeing so many children from COVID (isolation). Programs are full for next year already,” she said, predicting that many more children will be approved for a special education preschool over the summer. “What happens to those children when people don’t have the resources to open another classroom?”

She isn’t concerned about starting at a low rate for her new classroom. She knows it will eventually go up.

“The problem is not the philosophy (of the funding process), it’s that they are so backlogged,” she said.

Keen, owner of Abilities, kept expecting that her rate would increase soon to match her actual costs for the 2021-2022 school year.

“Then I find out, from the rate-setting unit, that the state is processing (rate increase requests) from other schools for the school year 2017-2018,” she said.

In the end, she closed before her rate was reviewed.

Mannion said he will continue to push for a new funding process.

“The system is rigged against them,” he said. “If schools cannot cover the costs ... then they close. That’s why we need this change in the long run, because the rates are not set until after the services are provided. What we need long term is to fix the rate methodology.”