Report calls for increased AIM funding for Rochester

The city of Rochester needs more state funding—at least at par with other upstate cities—if it is to thrive in the future, a new report from state Sen. Samra Brouk’s office concludes.

New York should give Rochester $13 million to $34 million more in annual Aid and Incentives for Municipalities funding, the report contends.

It argues that given the city’s systemic and urgent challenges, including gun violence and poverty, Rochester cannot improve the lives of its residents without additional funding. A delegation led by Brouk shared findings in the report with Rochester Mayor Malik Evans Monday.

“I’m proud to be working on this initiative with Mayor Evans and my colleagues in the Rochester state delegation,” Brouk said. “The data shows what many of us have known to be true—Rochester has been overlooked and underfunded for far too long.”

Evans commended Brouk and the local legislative delegation for “recognizing the connection between the inequity in the state’s revenue-sharing formula and the malady of poverty in Rochester. Rochester is home to three of the top five poorest ZIP codes in New York State, and state AIM equity would go a long way toward reducing crime and poverty, and increasing economic opportunity and access to education in our city.”

The report calls for a correction to the AIM funding disparity in the state budget. Rochester, a city of 211,000 people, cannot afford a per-capita funding stream well below its upstate counterparts, it states.

The $417 per capita funding rate for Rochester is lower than the $482 per capita rate for Syracuse, a city with 50,000 fewer residents, Brouk’s office notes. The state needs to address the difference, the report argues, by giving Rochester $13 million to $34 million more annually (to match Syracuse or Buffalo, respectively), and also provide a one-time sum of $130 million for the last decade of underfunding.

ources—the investments and wealth of the municipalities, organizations and individuals in those communities.”

A key component of addressing safety in the city is to consider a reversal of the state’s historic policy of disinvestment.

AIM funding, a revenue-sharing system, began 2006, and since then has seen changes. Typically, Albany, Buffalo, Rochester and Syracuse are the upstate that receive the largest share of these revenues. Brouk says one of these cities—Rochester—is underfunded in comparison with the rest.

Gov. Kathy Hochul’s executive budget proposes giving Rochester $88.2 million in AIM funding, compared with $71.8 million for Syracuse and $161.3 million for Buffalo. These amounts are unchanged from last year’s enacted budget.

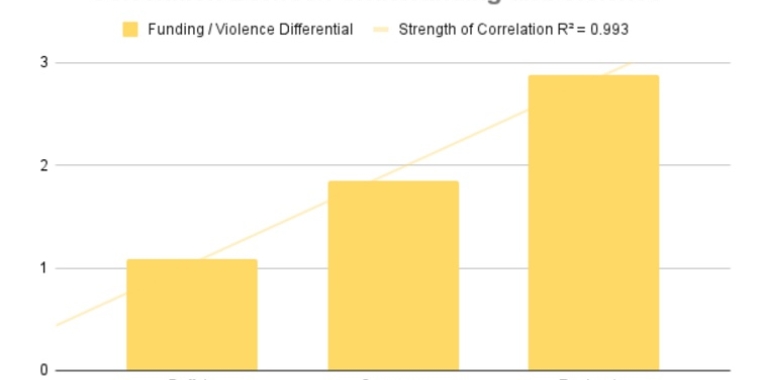

The report examines gun violence and poverty. The gun violence epidemic Rochester is experiencing is a multifaceted policy failure that needs as many potential solutions as possible, it states. While steps have been taken to curb the violence, these initiatives need to be combined with the necessary financial resources.

Well-resourced and -funded communities do not see the same levels of gun violence that Rochester experiences, according to the report. It uses 2021 data to compare upstate cities to demonstrate the high crime rate. Rochester was highest with 232 shootings and 53 fatalities that year. The other upstate cities, with smaller populations, saw fewer shootings and fatalities.

Child poverty, the report states, is another indicator of Rochester’s resource deficiency. In 2021, 48.2 percent of children in Rochester lived under the poverty level, the report says. Buffalo and Syracuse have comparable rates, 42.3 percent and 48.4 percent.

“However, Rochester does not see a comparable funding allocation based on its population and parity with the other cities. Likewise, child poverty rates this high paired with the current levels of gun violence, put Rochester into an immense negative feedback loop that will only be solved with the needed resources,” the report contends.

Child poverty not only can result in children being more likely to encounter violence, it also leads to higher rates of undiagnosed or untreated mental illness, and a lack of preventive health measures. If changes do not happen, the fatigue of these issues will only further break down the systems of support in Rochester—the resources needed to be delivered, the report states.

With extra funds, Brouk argues, the city will be able to begin tackling its daunting challenges.

Smriti Jacob is Rochester Beacon managing editor. The Beacon welcomes comments and letters from readers who adhere to our comment policy including use of their full, real name. Submissions to the Letters page should be sent to Letters@RochesterBeacon.com.